Breaking Down “The Decision”

You can understand why Carroll might be afraid of getting burned in what seemed like a hopeless situation for the opposition, because you only have to go back to Seattle’s last playoff loss to remember how quickly things can swing. That was during the 2012 playoffs, when the Seahawks came back from a 27-7 deficit in the fourth quarter to take a 28-27 lead with 34 seconds to go. In that game, the Seahawks handed the ball to Lynch on first-and-goal from the 2-yard line, and he immediately scored.

Despite the stunning comeback, Atlanta got the ball back with two timeouts, completed a pair of passes, and got a 49-yard field goal from Matt Bryant to win the game. The Packers, furthermore, responded to another huge Seattle comeback by taking over with 1:19 left and driving for a game-tying field goal in the NFC Championship Game. I’m not arguing that Carroll and offensive coordinator Darrell Bevell should have been so time-conscious as to basically waste second down on a pass play. But I can understand why they would be overly sensitive about leaving too much time on the clock.

If you’re thinking about the game coming down to those three plays, you can also piece together a case that second down is the best time to throw the ball. As Wilson took that fateful second-down snap, there were 26 seconds left and Seattle had one timeout. Let’s pretend for a moment that the Seahawks decide to run the ball on second down. If they don’t get it, they have to call timeout, probably with about 22 seconds left. That means they’re stuck passing on third down with virtually no chance of running the ball, because it would be too difficult to line up after a failed run.

On the other hand, by throwing on second down, you could get two cracks at running the football while providing some semblance of doubt for the Patriots. If Wilson’s pass on second down is incomplete (and he avoids a sack, which seems likely given his ability to scramble), the clock stops with something like 20 seconds to go. That means you can run the ball on third down, use your final timeout, and then run the ball again on fourth down. All three plays come with the possibility of either throwing or running, which prevents the Patriots from selling out against one particular type of play.

You might argue that the logic there doesn’t include the danger of throwing the football and the downside of an interception, and that’s true, but there are negative possibilities in every play call. In fact, this season it was more dangerous to run the football from the 1-yard line than it was to throw it. Before Sunday, NFL teams had thrown the ball 108 times on the opposing team’s 1-yard line this season. Those passes had produced 66 touchdowns (a success rate of 61.1 percent, down to 59.5 percent when you throw in three sacks) and zero interceptions. The 223 running plays had generated 129 touchdowns (a 57.8 percent success rate) and two turnovers on fumbles.

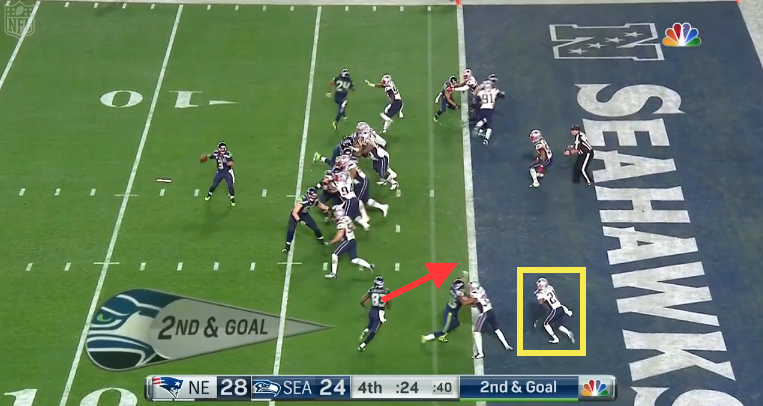

Carroll claimed after the game that the Patriots were in their goal-line package and that the Seahawks, who came out with three wide receivers, were right to throw the ball and basically waste a play against a mismatch of personnel. I’m not sure I see that, and Belichick confirmed as much after the game. The Patriots did line up with a combination of eight defensive linemen and linebackers in the box, seven of whom were on the line of scrimmage at the snap, but they also played three cornerbacks — Malcolm Butler, Darrelle Revis, and Brandon Browner — against Seattle’s three wideouts.

Rookie cornerback Butler did a great job of breaking on the slant for what will surely be the biggest interception of his life. As you can see from Sheil Kapadia’s tweet below, Butler had a lot of work to do to break up the pass once the ball was in the air, let alone actually make the interception:

The space you see in the screenshot makes Ricardo Lockette seem more open than he actually is — Butler has already identified on the route and he’s going to drive on the football — but it’s not as if Wilson made a dangerous throw into traffic. If the Seahawks really wanted to waste a play, as Carroll was suggesting, Wilson could have thrown this into the ground or thrown it through the back of the end zone. He didn’t because they got the exact look they were hoping for.

In terms of execution, I’d assign more blame to Lockette, who got beaten to the spot and knocked to the ground by Butler, a player Lockette outweighs by 20 pounds. As galvanizing as it’s been over the past 12 months for the Seattle wide receivers to contrast their no-name status with their success, this was a game when the team’s need to upgrade at receiver was clear.

So, that's where I think Carroll was justified in his play calling. Barnwell goes on to argue, however, that given the porous Patriot run defense and Lynch's unstoppability at the time, it was still a "subpar decision". I'm not so sure I agree.

No comments:

Post a Comment